Let’s take a trip back five years ago when I created a special board game for my students. It was a game-changer! The game was designed to assist students in constructing understanding by visualizing connections among related concepts. In this article, I invite you to relive the excitement and insights from that memorable experience and explore how personalized board games can become a catalyst for learning.

The Dilemma: My students explored several concepts related to energy during the science lessons; What is energy? fuels and their usefulness, non-renewable vs renewable energy resources and use of energy by living things. At the culmination of the unit, the summative task asked an open-ended question, ‘How the Sun’s energy from millions of years ago be transferred to electricity today?’ The results of the task showed that many students could not make sense of or relate to the various ideas of energy and appreciate its impact on our lives.

Faced with this challenge, I had a decision to make: should I proceed to the next unit, or should I pause for a little while and use a more effective strategy to enhance their comprehension? I realized that what we needed was a unifying framework that could tie together all these energy-related ideas into a coherent whole. And that’s when the idea of creating a board game as an alternate teaching and learning method came to light!

Why a Board Game? The constructivist learning theory advocates for the construction of knowledge by exposing children to various information sources and opportunities to collectively observe and analyse information or ideas, promoting active learning rather than passive absorption. Educational games such as board games, can stimulate their observational skills and cultivate higher-order thinking abilities-a crucial aspect for encouraging effective inquiry. Furthermore, children often become personally engaged with specific aspects of a game while adhering to the established rules and desired curriculum content, thereby ensuring a deeper level of learning. However, an educational game that fits a specific curriculum objective may not be readily available or produced commercially. As this was the case, I decided to create a game of my own; all that was needed were pens and colours to put the big idea on paper.

Generating the Big Idea: To create a game, I needed a central theme, often referred to as the ‘big idea’. This concept serves as a unifying principle that connects and organizes numerous smaller ideas, concepts and experiences, making it a powerful tool in teaching and learning. To make my big idea more generative, I aimed to move beyond established facts and topic headings, seeking to frame ideas that provoke thoughtful responses. So, instead of solely adhering to the overarching idea that ‘Sun is the ultimate source of energy’ which was effective but somewhat limiting in connecting various topics, I rephrased it as the ‘Journey of energy from the sun to an electric bulb’. This action-oriented statement served as a foundation for organizing key concepts within the energy unit under study. It helped establish a narrative structure encompassing a series of events (teaching points).

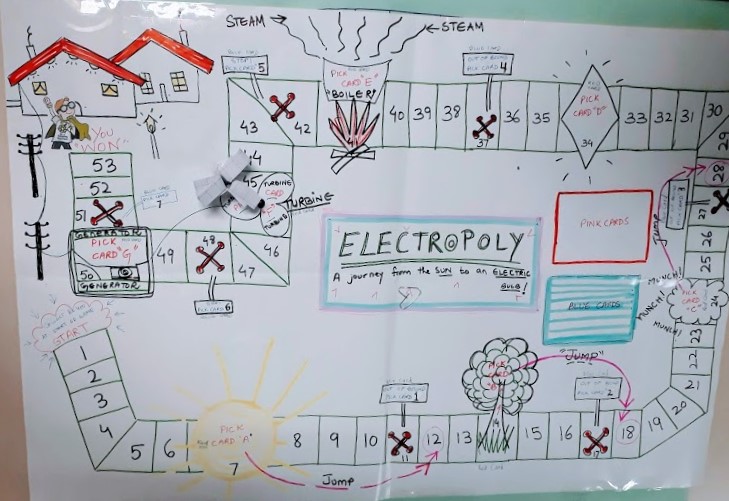

Game Design: The vision was brought to life with a board game called ‘Electropoly inspired by the famous Monopoly. The game was designed with a simple and progressive gameplay style, where the different topics related to energy are linked as a series of events. To make it more engaging, pictures were added to the board to create a more visual learning experience, stimulating students’ imagination and enhancing comprehension. This game brings together all the separate energy concepts studied and combines them into a single unit, guiding students through a narrative-like progression that helps them see patterns and interpret connections among them.

The Play: During gameplay, emotional engagement was evident as the air buzzed with excitement. Students worked in groups of four; using game pieces, dice, play money and energy facts cards. Each card not only moved them forward but served as a mini-lesson in itself, sparking discussions. Checkpoints along the game’s path presented challenges and required recall of certain energy facts. A standout moment was when a student connected the dots between photosynthesis and solar energy. His eyes brightened as he excitedly explained to his peers how this process converts sunlight into the chemical energy we find in our food. Another student went from hesitating about the energy unit to leading discussions on the game board, showing how this game transformed learning into an emotionally charged collaboration.

I was delighted to see how this shared experience created by Electropoly was more than just educational; it was transformative. The laughter, discussions and insightful moments made the concepts of energy memorable, proving that learning can be deeply engaging and fun.

Closing the game: I played the role of a monitor and facilitator during the game, listening to the conversations and taking note of any misconceptions. The use of games as a teaching tool is only effective as long as it is supported with some instructional support like prompting, feedback, reflection and debriefing. So, after the game, we had a debriefing session where students discussed what they had learned, reflected on the concepts, and addressed any misunderstandings. This process helped consolidate their knowledge and improve their understanding of energy-related concepts. It also highlighted underlying principles, such as the fact that energy is present in both living and non-living things, it cannot be created or destroyed, rather transformed from one form to another.

The Impact: The game had a significant impact on the students learning. In subsequent assessments of the same question, students demonstrated remarkable improvement. They confidently used scientific vocabulary, created infographics, wrote explanations, and described how the Sun’s energy can be transformed into electricity. It was clear that the game had effectively enhanced their understanding and retention of these complex concepts.

Sky is the Limit: This game aimed to deepen children’s comprehension of concepts they had already learned, acting as both an enrichment activity and a reinforcer for recall by integrating the main idea and teaching points at the unit’s end. Additionally, such games can serve as conversation starters or front-loaders at the beginning of a unit, familiarizing learners with essential vocabulary. Introducing games at any point in the lesson invariably brings joy and enhances learning. Crafting well-conceived conceptual games represents a significant investment in time and energy but pays off by enriching the educational toolkit with resources that can be reused across various contexts. Although this discussion focuses on science, I believe the principle of designing games around big ideas can be applicable across subjects, offering a versatile solution with widespread benefits.

Special Thanks: To Kiran Qasim Ali, Workshop Coordinator at Making Science Learning Fun, for providing the inspiration to create this game.

Read Part 2-Click here: Creating Boardgames to Improve Learning (part 2 of 2)

References:

Jan, H., & Heinz, M. (2012). Learning in or with games? Quality criteria for digital Learning Games from the Perspectives of Learning, Emotion, and Motivation Theory

Whitton, N., & Moseley, A. (2012). Using games to enhance learning and teaching: A beginner’s guide. New York: Routledge. Doi: EBOOK ISBN 9781136341311

Leemkuil, H., Jong, T., & Ootes, S. (2000, September). Review of educational use of games and simulations. The University of Twente.

Zhou, M., & Brown, D. . (2015). Educational learning theories: 2nd Edition [Education open textbooks]. Galileo Open Learning Materials.

Zohar, A. I. (2013, November). Inquiry learning as higher-order thinking: Overcoming cognitive obstacles. . What Issues arise with inquiry learning and teaching, Part 3, 405-424.